AWS Lambda - HTTP APIs and Concurrent Requests

Are you hosting your HTTP API in a AWS Lambda? Are you aware of AWS Lambda concurrency model regarding HTTP concurrent requests? Let’s investigate.

HTTP APIs

When you build a HTTP API using your preferred language and HTTP framework, you expect that the HTTP framework will live in a process which will handle multiple concurrent requests, right?

When it comes to AWS Lambda that doesn’t happen: one instance of a AWS Lambda processes one HTTP request at a time.

You are maybe asking now: what happens then if a second HTTP request comes in while still processing the first request? Well, the second request will be handled by a different AWS Lambda instance. This 2nd AWS Lambda instance can be a new one, if no instances are ready, or an existing one that is idle (not processing requests) and ready to process the new request (because it has handled a recent previous request). This is all done magically and under the hood by the AWS Lambda service.

Is this really a problem? I don’t think so. However, I think it is counterintuitive at first because it’s not what we are used to when handling HTTP requests. I think it’s a smart design indeed, because the computing becomes more predictable since every instance only handles one request at a time.

So, what are really the consequences of this design? Maybe we will have more cold starts than we were expecting, particularly in cases where we have a burst in concurrent requests.

Cold Starts

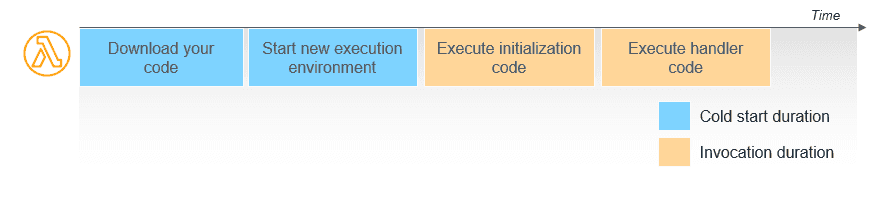

A cold start happens when a new AWS Lambda instance is required to be created to

handle the request coming in, mostly because there are no AWS Lambda instances

ready available. When this happens, the AWS Lambda service needs to spin up a

new execution environment with the memory, runtime, and configuration specified

in the function. Once finished, AWS Lambda runs any initialization code - in

HTTP APIs means running the bootstrap of the framework, typically registering

services in Dependency Injection (DI) containers, configuring HTTP midleware,

etc (the code in Execute initialization code below).

When an instance finishes to handle a HTTP request, the instance is kept warm

and ready to handle another HTTP request. In subsequent HTTP requests, if a warm

instance is available, only the Execute handler code is invoked. If no HTTP

request comes in for a while, the AWS Lambda service will eventually destroy the instance

after a while of inactivity.

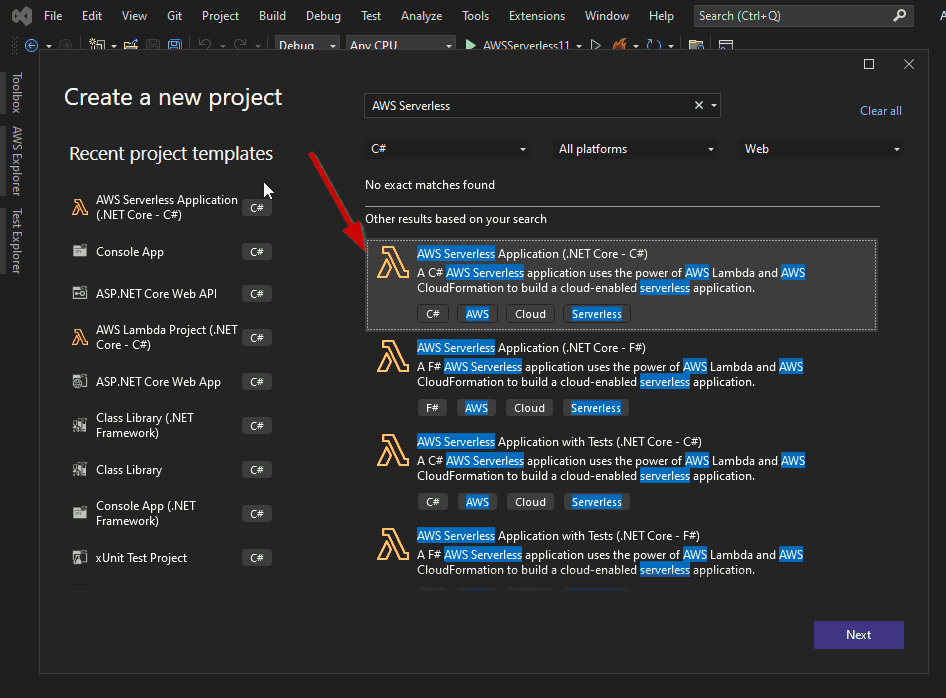

We can build something really quick to show this behavior. I am going to ilustrate the steps with a ASP.NET Core 6 Minimal API. You need to have installed the AWS Toolkit for Visual Studio 2022.

-

Create a new AWS Serverless Application (.NET Core - C#) in Visual Studio 2022

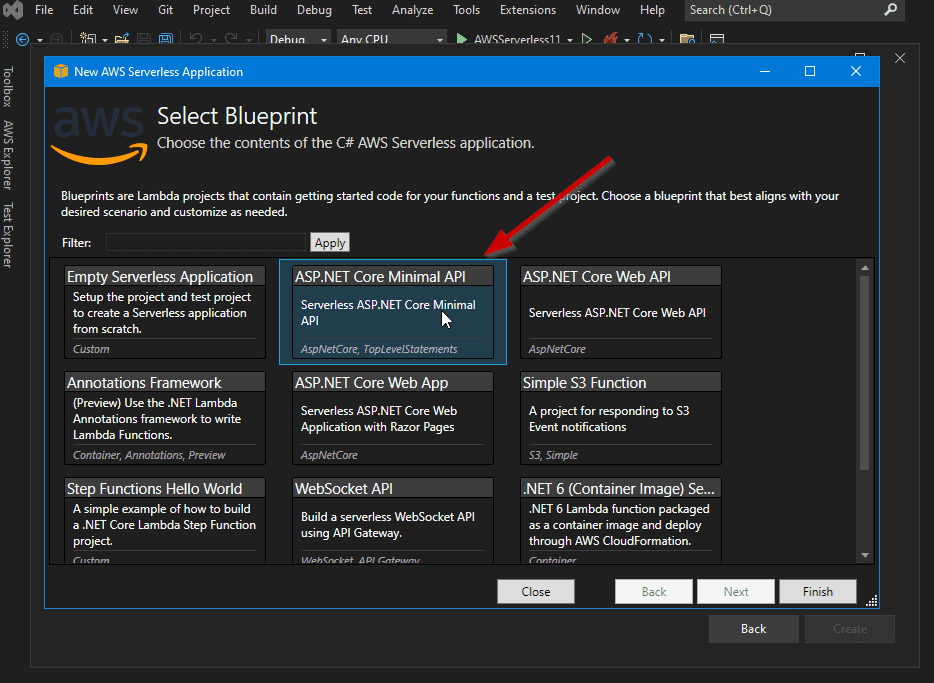

-

Select the Blueprint ASP.NET Core Minimal API

-

Change the code to add some delay while serving a HTTP request to give us time to launch new requests.

On file

Program.csreplace the lineapp.MapGet("/", () => "Welcome to running ASP.NET Core Minimal API on AWS Lambda");by the following code

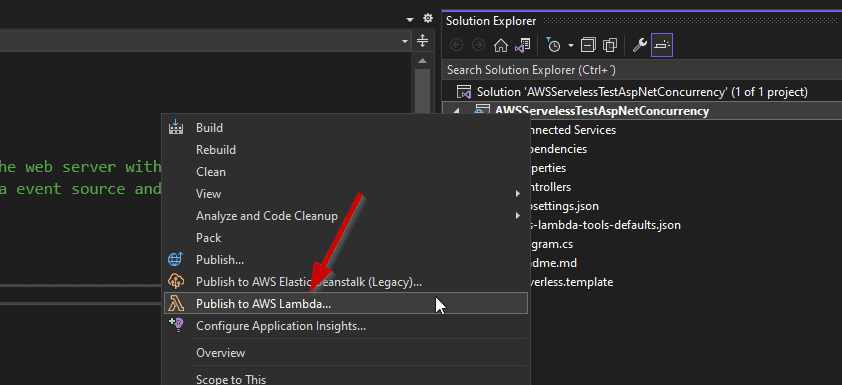

app.MapGet("/", async () => { // Wait 5 seconds await Task.Delay(5000); return "Welcome to running ASP.NET Core Minimal API on AWS Lambda\n"; }); -

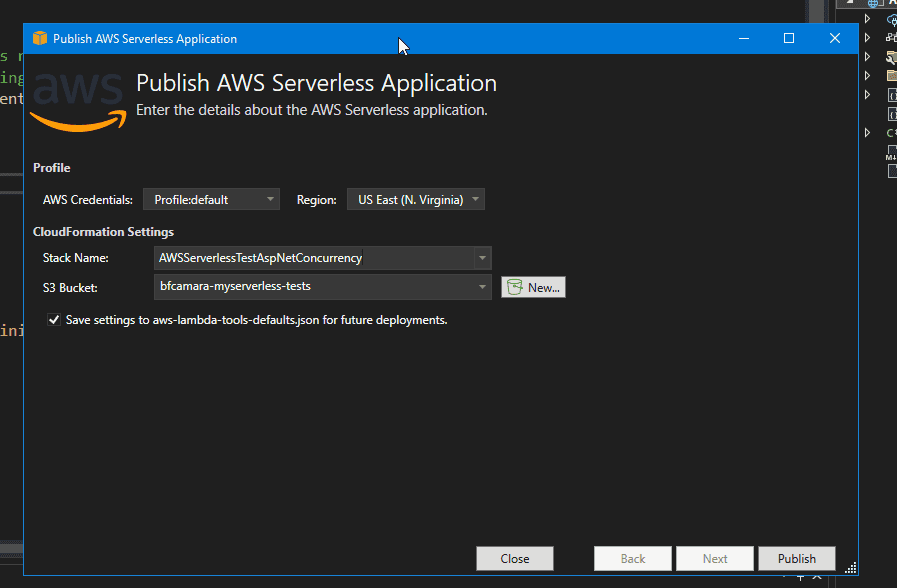

Publish to AWS Lambda

Give a name to your stack (a stack is a group of resources representing a serverless app).

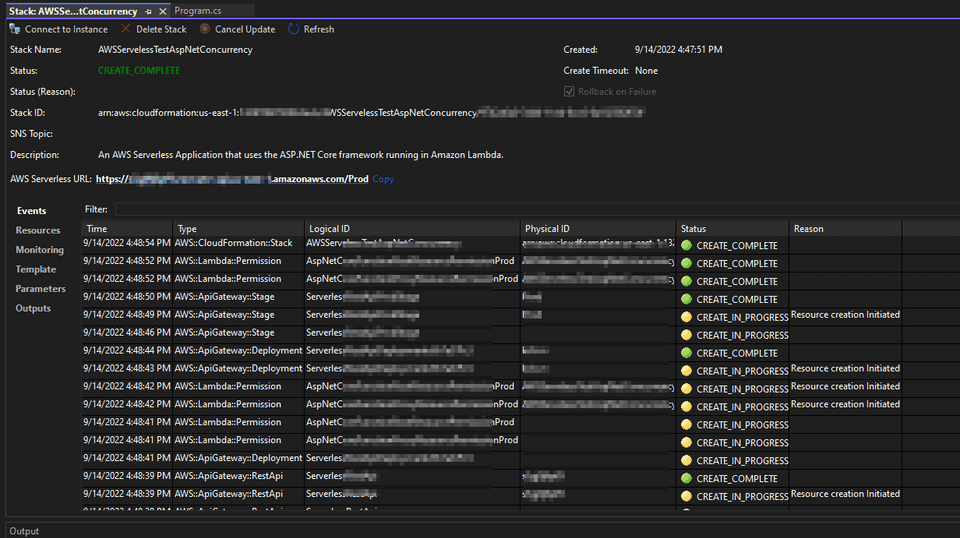

You can follow the deployment progress and once finished you should see the Stack view tab

-

Test your endpoint in the browser

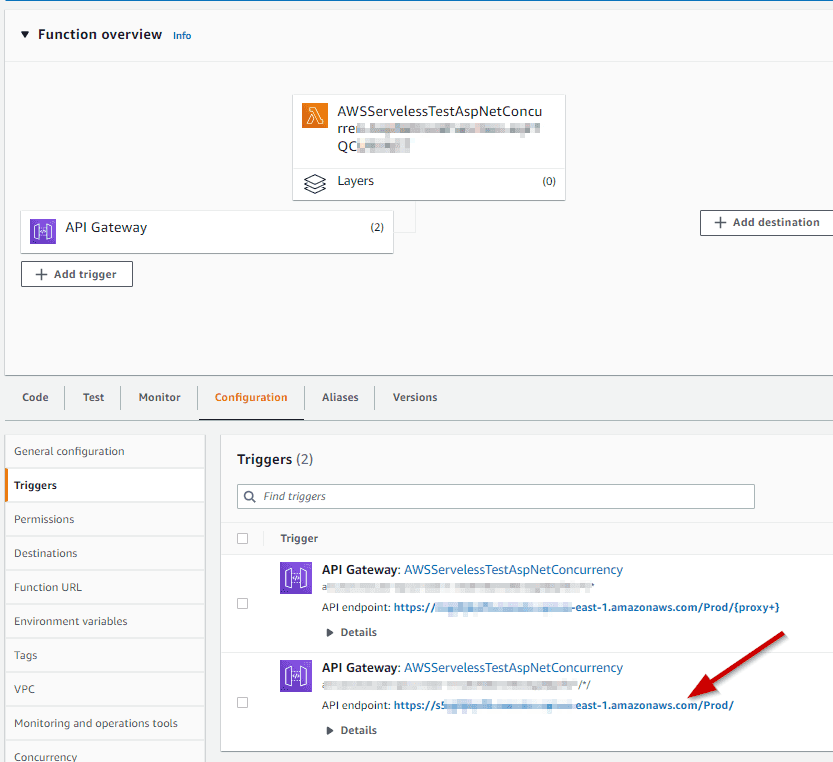

The stack that was created includes an API in AWS API Gateway. You can check the URL in the Lambda page that will trigger the function.

Click on the link and you should wait aprox. 5 seconds until you have the answer in your browser.

-

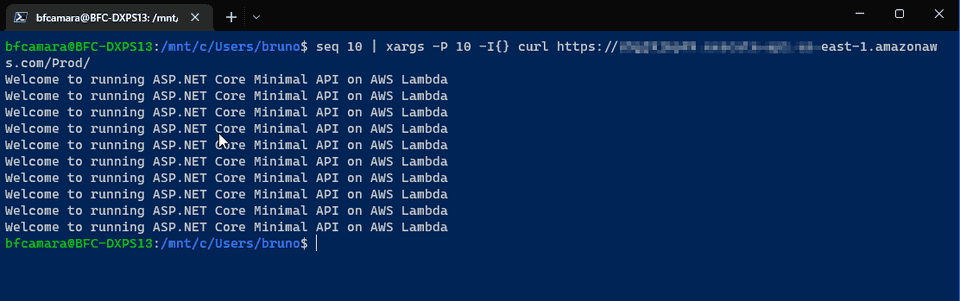

Launch 10 concurrent requests

At this point we should have a AWS Lambda instance ready to handle more requests. So let’s launch 10 simultaneous requests to see what happens. Open a bash or a windows subsystem for linux (wsl) and run the following command

seq 10 | xargs -I{} -P 10 curl <url_api_gateway>The requests are launched concurrently, wait aprox. 5 seconds, and you will see something like this.

-

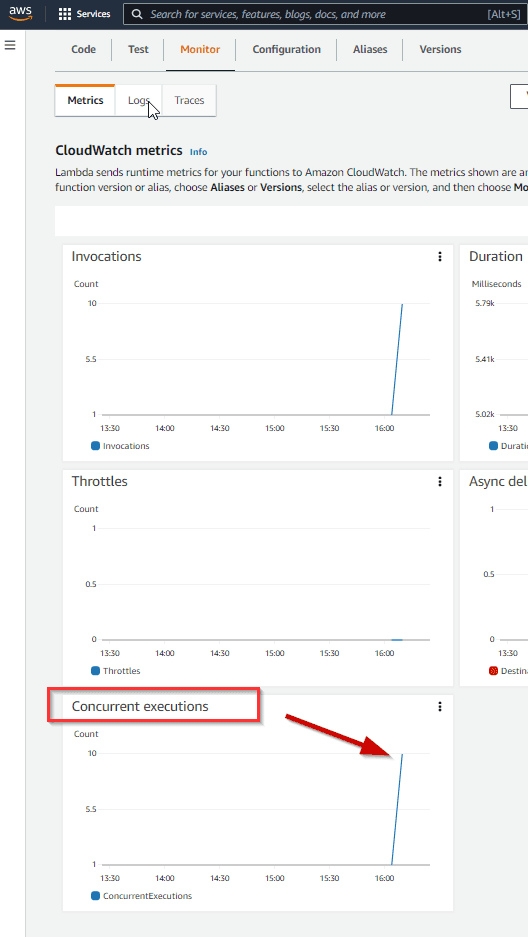

Monitoring concurrent executions

Now it’s time to check what happened in terms of number of instances. Probably you were expecting that the instance that served our first request in browser would be used to serve all the concurrent requests. But as I’ve mentioned before, it’s not what happened. We can check the Monitor -> Metrics tab in the function page.

As you can see the AWS Lambda service has created 10 execution environments.

-

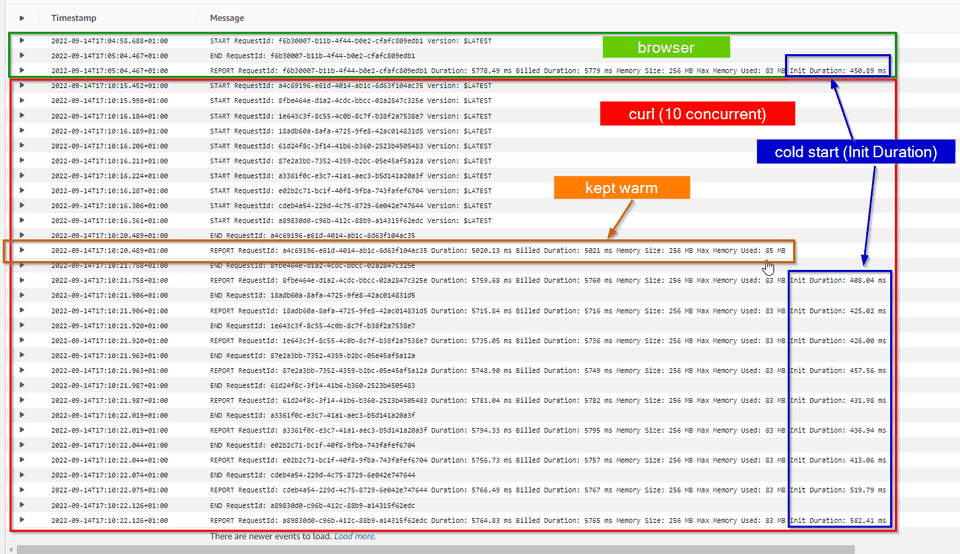

Check number of cold starts

On total we have made 11 requests, one initially in the browser, and then 10 with

curl. Let’s see what the logs are saying (AWS CloudWatch logs).The intial request (browser) was served by a new execution environment, so we had a cold start. A cold start is easy to identify in the logs by searching for a

Init Durationin theREPORTlog.Next, when we launched 10 concurrent requests, the first request comming in reuses the execution environment that was created for the initial request completed in the browser (the instance was kept warm). For the remaining 9 requests the AWS Lambda service has created new 9 execution environments, hence 9 cold starts.

When building synchronous APIs like a HTTP API, we want to avoid cold starts, particularly if it’s a customer facing API, because it will include more latency in the whole request-reply flow. But a cold start is almost inevitable if we want a scale to zero approach and avoiding to pay for resources when there is no activity (HTTP requests).

Minimizing Cold Starts

To minimize the impact of cold start we can:

- Reduce the number of cold starts

- Reduce the time of a cold start

To reduce the number of cold starts we can use Provisioned Concurrency. Provisioned concurrency initializes a requested number of execution environments so that they are prepared to respond immediately to your function’s invocations. Be aware that configuring provisioned concurrency incurs charges to your AWS account.

To minimize the time spent in a cold start there are some things we can do:

- keep our package small

- minimize library dependencies

- adjust memory function (you can use AWS Lambda Power Tuning)

- be lazy in initialization

Can your HTTP API live with Cold Starts?

It really depends. First, we need to measure the cost of a cold start in terms of latency. For example, the logs above are showing that a cold start takes aprox. 500ms (for a very simple scenario). A cold start duration varies based on programming language, runtime, etc.

Second, we need to understand how our API is being used by consumers, who are these consumers, and what are the patterns of usage during the day, day of week, etc. Based on that knowledge we can have an idea of what is the impact of a cold start in the flow in which we are using our function.

If we anticipate problems caused by cold starts, we should analyze what is the cost (money) of configuring provisioned concurrency. Furthermore, consider using Provisioned Concurrency with Application Auto Scaling to adjust the number of provisioned instances based on usage. Nevertheless, we need to be aware that we will be charged by using provisioned concurrency.

AWS Serverless alternatives to AWS Lambda

If we are not confortable with the concurrency execution model provided by AWS Lambda, we can always use some alternatives in AWS:

-

AWS App Runner - a fully managed container application service with auto scaling based on Max Concurrency - we define the max number of requests that will trigger the scale-up process. The AWS App Runner uses the normal execution model where a container instance can serve multiple concurrent requests. There is always at least one instace provisioned.

-

Fargate with AWS ECS or AWS EKS (Kubernetes) - We are probably already using Kubernetes or any other container orchestration engine, so we can always use it to host our HTTP API. This route provides more flelibility and full control, however is the route that is more complex.

Conclusion

When analyzing a specific scenario, AWS Lambda is typical the option that I consider first in AWS when going serverless . It’s really simple to use, integrates seamlessly with a lot of AWS Services (SQS, S3, SNS, CloudWatch, API Gateway, etc.), and provides a lot of great features specially when it comes to scalability: scale-up or scale-down (scale to zero).

If we want a “scale to zero” approach, then we need to be aware of cold starts, particularly in case of synchronous APIs, where it can cause some impact in terms of latency. If the scenario being analyzed cannot live with cold starts, I would consider using AWS App Runner which has a very interesting pricing model.

Regarding Kubernetes (AWS EKS), I think it makes totally sense when it’s an initiative enterprise wide. The learning curve is not negligenciable (even when we don’t need to install and administer the cluster like in AWS EKS), and typically we need to spend some time configuring the cluster until we have all the knobs needed. For example, if we want to have auto-scale based on events we might need to have KEDA installed (that’s exactly what Microsoft did with Azure Container Apps).

See you next time. I will continue to explore other scenarios like gRPC and WebSockets.